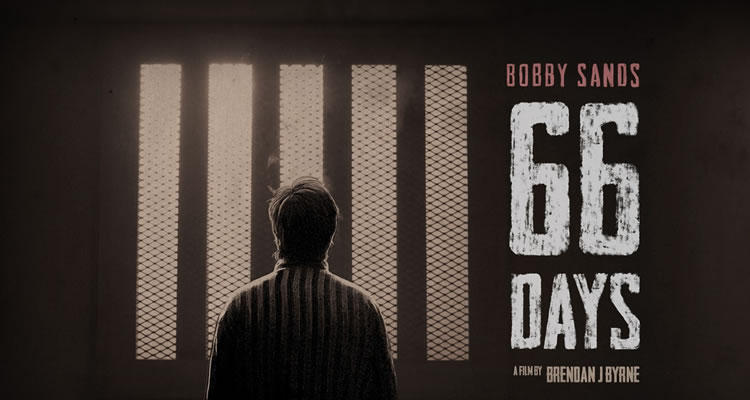

This week sees the release of a new documentary about the 1981 hunger strikes in Northern Ireland; ‘Bobby Sands: 66 Days’. Told through the eyes of friends and contemporaries of Sands, as well as interviews with Fintan O’Toole and Gerry Adams, to name but two, ‘Bobby Sands: 66 Days’ shines a light on the person at the centre of the hunger strikes, a man who died for his beliefs, 27-year-old Bobby Sands.

Movies.ie sat down with filmmaker Brendan J. Byrne to find out more about his intriguing and balanced documentary, which had it’s Irish premiere at the Galway Film Fleadh last month.

Bobby Sands’ story is well known, in a way, and has been covered in films including ‘Hunger’ and ‘Some Mothers’ Son’. What made you want to tell this story again?

Brendan J. Byrne: You say it’s a really well known story, in a way, and the hunger strike is a well known story, but Bobby Sands himself, I feel, was a blank canvas. He’s a picture on a wall, he’s well known as the first hunger striker; most people didn’t know he wrote a diary, most people didn’t know what politicised him. So I felt that while I loved ‘Hunger’ as a film, and I knew there were other films that had been made about Bobby Sands and the hunger strikes, I thought there was a real narrative deficit about Bobby Sands. He’s a figure that’s in our imaginations, we do have the picture of him in our mind, but if we actually stop to think about what it means, or what is the story behind it, we’d run out of road quite quickly.

Did the Sands family have any input into the film?

BJ.B: No, I went to speak to them and asked them would they participate. I talked to them at length, the two sisters and Bobby’s son, and after a long meeting they came back to me and politely declined. They haven’t really contributed to anything – television, book or movie – certainly not since 1985 to my knowledge. They are very private, they are very respectful, I think they want to protect an element of the family memory, keep that to themselves, and I respect that. I offered to show them the film before anybody else in the world saw it, they politely declined that as well. I have had an engagement with the family, I have done everything I can to ask them both to participate and to see the film, but unfortunately they declined. There is certainly no hard feelings there, and I hope myself that in times to come they will see the film and they will recognise that it is a very honest and earnest piece of work, which whilst not being a tribute film, is certainly something that sets their brother in the canon of Irish and international history. I think that in years to come they will hopefully come to appreciate that themselves.

The film is remarkably balanced, has the potential to change how people see Bobby Sands. How did you find that balance within the film?

BJ.B: That was difficult. I know people have been fed particular narratives, and this is about offering you a narrative that is non-partisan, but it is challenging you to think about the accepted narrative that you have taken up until this point. I knew that this film would be killed if it didn’t have balance, but balance for balance’s sake can be quite boring. With the BBC as one of the significant funders of the film they cannot put out material which isn’t balanced. I am a catholic, I was born and grew up in a catholic tradition, my wife grew up in a protestant tradition; how could I live at home if she thought it wasn’t balanced? She only saw it for the first time in Galway [Film Fleadh], I still don’t know what she thinks of it fully; that’s going to be a conversation for the weeks and months to come. Balance is important, but not balance for balance’s sake.

While making the film, did you find anything out about Bobby Sands that surprised you?

BJ.B: I think one of the things that I learned most was, I had always thought that the decision to go on the second hunger strike, after the first failed hunger strike was a more widespread Sinn Fein and IRA decision. What I found out was not only was he brave by being prepared to go on hunger strike, but I see in that moment the reasons why he has become the image on the wall; he stepped forward at that moment and became a leader. He became a leader in the face of the opposition of a movement he loved but also was prepared to challenge. The certainty at that age and the idealism is just staggering.

Was it a deliberate decision to release the film in the 35th anniversary year of Sands’ death?

BJ.B: No not at all. We were just making the film. We knew 35 years was floating, anniversaries can be useful, so it wasn’t overly calculated. The general period of 34, 35, 36 years we felt was a good time to look back at these events, and to re-examine them because it is 20 years since peace, and hopefully people can look at it in a way that, without being overly burdened by their baggage, are prepared to shed their baggage and think of it in a deeper sense, which might not have been possible 10 years ago.

The film screened at Hot Docs in Canada and the Sheffield documentary festival before it came to the Galway Film Fleadh. Were the reactions very different in these three places?

BJ.B: Strangely enough, they haven’t been incredibly different. The general reaction to the film has been very strong. I think in Galway you could say it was a bit more additionally emotive. You could feel the emotion more in the audience, it was palpable. It was more charged and a bit deeper and a bit more emotional, but not wildly different. I think there has been a uniform appreciation and engagement with the film, it’s just the emotional number of the dial has been dialled up a bit.

What do you hope audiences take from the film?

BJ.B: Specifically I’d love for people my age, who think they lived through it and have had a narrative of it that’s accepted, to get off the stereotypes and to get off the accepted narratives that we have all lived with and all taken as a staple diet. Without being provocative, I want the film to challenge each of out status quos. Then I am really interested in the younger generation seeing it and I’d love young people to go and see this film, north and south. North in particular, only in the sense that all of the 20-year-olds parents would have lived through that period, they will have heard their own narrative that has been passed down; that’s what happens in historical conflicts.

Words: Brogen Hayes

‘Bobby Sands: 66 Days’ is released in Irish cinemas on August 5th 2016. Watch the trailer below…