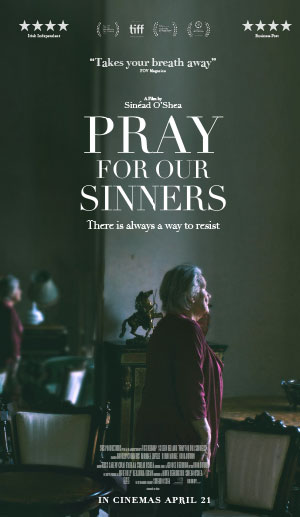

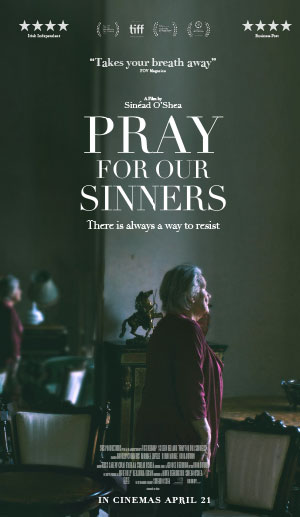

Prayer for our Sinners looks at the damage done by mother and baby homes and the effects of corporal punishment by examining the stories of Norman, Betty, and Ethna, three people supported in their hometown of Navan by doctors Paddy and Mary Randles. They joined together to form a quiet band of resistance at a time when the Catholic Church ruled the country with fear and coercion. Paddy and Mary went against the grain, calling for an end to corporal punishment and supporting women and girls to keep their babies despite being institutionalised in homes. Director Sinead O’Shea tells us more.

Why tell this story?

It was time to tell the story of what happened in Ireland between the church and the people in an intimate way. We usually hear about it on a national scale, but this is about a small group of people and how they were affected. But, also, they are stories of resistance, of people who fought back against the system. They can’t be the only people who fought back, and I hope by telling this story, others might come forward and share their stories of resistance. We need to celebrate these stories and recognize them.

It is a difficult subject to discuss; how did you get people to come forward and share their stories?

A school friend suggested that I talk to Dr Mary Randles. Mary was keen for the film to be made to celebrate her husband Paddy’s life; she didn’t really see how important her role was. As I got to know Mary, I realised how much she had done. Mary very casually told me one day that they used to hide young women in their house to keep them out of mother and baby homes. When I heard this, I thought it was the most amazing story and that it would be really good to talk about this in this documentary. I asked Mary if she still knew any women who had an experience with the homes and if they would be willing to talk to me on camera. So, it was through Mary that I met the other people in the film, and it was thanks to her; they were willing to open up. It helped that I am also from Navan, so I wasn’t a total stranger even though they didn’t know me.

Are you worried about telling a story like this about your hometown?

I am a little bit because, but there’s an awful lot of affection for the Randles in Navan, so I don’t think anyone will object to their work being celebrated. There’s a lot of pride there for what they did. There’s a storyline involving the old parish priest, which many people wouldn’t be aware of. It’s quite a nuanced story because he’s not all bad but not all good. Not all priests were monsters, some were, but others were capable of doing good and bad deeds. The parish priest referenced in this fits in that grey area. That’ll be the talking point, I would imagine.

For your previous documentary, A Mother Brings Her Son to Be Shot; you spent years filming the family involved. Was shooting Sinners a long process?

No, it wasn’t as necessary because the stories we were telling had already happened, unlike the previous documentary where we were almost following events as they happened. This film’s primary purpose was to tell the stories of what had happened as part of a resistance that Mary and Paddy had been fighting. The main job of the film was to tell Norman, Betty, and Ethna’s stories. It didn’t really make sense to spend more time with them. What happened to them all those years ago has been very much defined by them, for good and for bad. I wanted to document and celebrate those stories because there’s a lot of positivity to those stories. They are stories of resistance, resilience, and bravery.

You use a lot of archive footage in the film, but you had a small budget. How did you navigate the finances to include as much as you did?

The archive footage was essential to setting the tone, but it was a nightmare because our budget was so small the footage cost us a quarter of our whole budget. We found some of it in the IFI, and there was some footage from RTE that I was keen to use. The most important piece of footage is from an American documentary shot by NBC; you will see it in the documentary; they came here to film a segment on corporal punishment. It is incredible to see all the schoolchildren talking about being beaten, and in the next frame, all the teachers deny the use of corporal punishment. It’s a vital piece of footage, it took a long time to track it down, but it was worth it. We also put a call out to local people asking for any footage they had, and we were given some home videos.

Was filming during the COVID lockdown tricky because you were working with people who are high risk due to their age?

Ironically, the whole thing was facilitated by COVID. When we started, the film was given some development money from Screen Ireland as part of a COVID relief scheme, but we couldn’t get a crew together because it was such a small film. I went back to Screen Ireland and applied for what’s called a micro-budget, which is the smallest budget Screen Ireland has; it means you can’t work with any other financiers, and you have to stick to this very small budget, but the advantages are that you get to work straight away. When we started filming in Navan, the entire town was shut down by COVID, it felt quite apocalyptic. It was this small film shot during this mad time, and unexpectedly we ended up showing it at the Toronto Film Festival; it was just crazy. It was the most unlikely thing I could imagine. If you had asked me mid-lockdown, I would never have thought we would get the chance to travel with the film.

The film screened at the Dublin International Film Festival; what was it like to bring it home?

The screening was brilliant. We’ve brought it to American festivals, and it did well there, but I knew it would be read differently by Irish audiences because it is about something that happened here. I was very nervous, but it was a wonderful screening, and it was a very emotional screening. Some people just had tears on their faces; it is incredible to see the film you worked so hard on have an impact. There was a standing ovation at the end. It was a fantastic experience which completely exceeded our expectations. In the days leading up to it, I was thinking, I don’t think I’m cut out for documentary work, I was that nervous, so it was great to see it received so well.

What impact would you like the documentary to have on audiences?

This might sound idealistic, but I would like them to think about what bravery or resistance means. It’s so heroic to do things like that when the stakes are so high. Mary and Pat Randles took action when it could have damaged them so much. It was an incredibly difficult time to resist. They risked their professions, their home, and their economic certainties to go against the church. I would like the audience to celebrate the goodness of people and think a bit about what brave moves they could make. It is a big ask, but even if they just thought about it, it would be a big step towards change.

Words – Cara O’Doherty

PRAY FOR OUR SINNERS is at Irish cinemas from April 21st